05 - Process API - Part II

Outline

- Process synchronization using

wait()- Allows for a process to wait until the status of a child has changed

- Can do more than just that

- You read the exit code of the child (find out what happened to the child, i.e, got killed, exit gracefully, etc.)

- Zombie processes

- If the child finishes first before the parent calls wait() the child becomes a zombie (just hangs out)

- Zombie process prevention

Intro

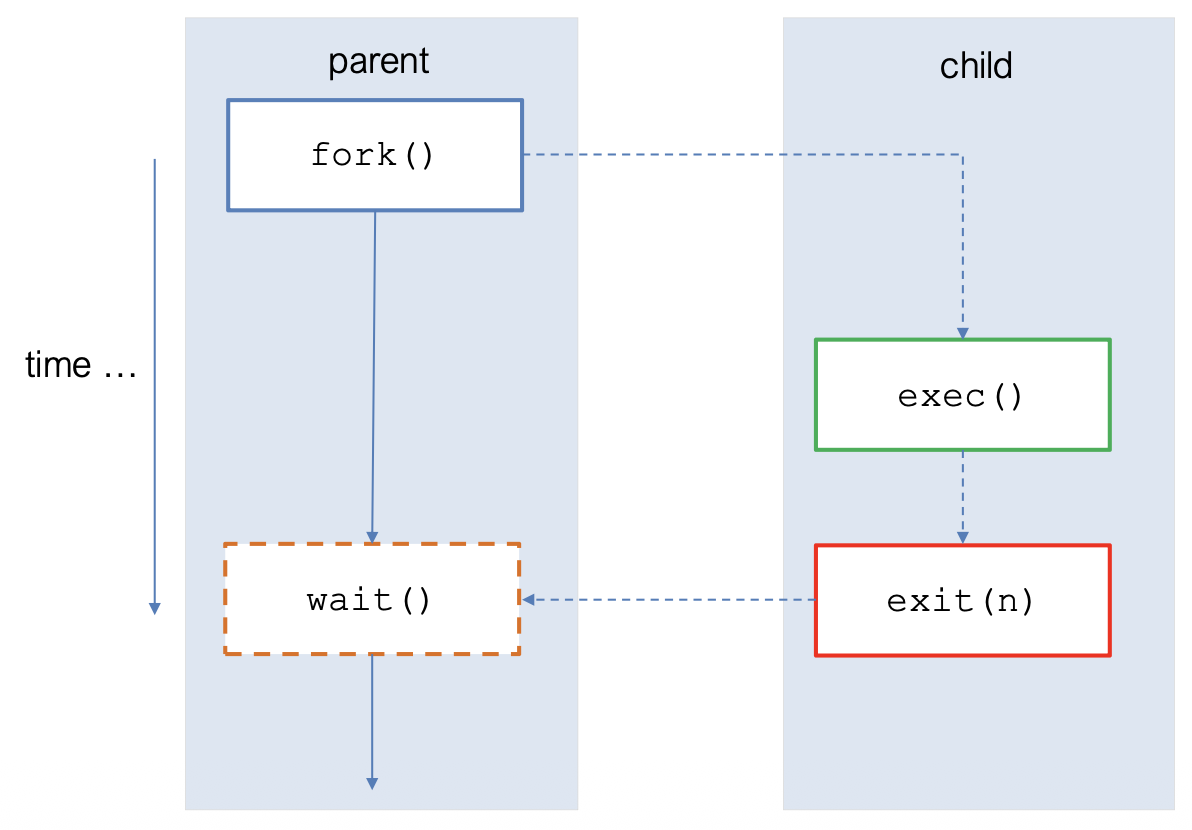

- In part I, we used

fork()andexec()to create new processes. - However, we do not know the order of their execution since that is dependent on OS scheduling.

- We are still missing the parent-child dependency where

- the parent waits for the child to complete before proceeding further.

Process synchronization

- Because of cloning, everything after the fork() is executed twice, once in the parent and once in the child. "Hello" prints once while "Bye" prints twice.

- The shell (ID=74907) is the parent during the first two prints.

- Process IDs are assigned sequentially and recycled after process termination.

- After the child is created, the schedule of the parent and children are independent i.e., the parent or the child might be scheduled first.

The program below lacks synchronization between the child and the parent.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello!! My ID is %d, my parent ID is %d.\n",getpid(), getppid());

pid_t pid = fork();

printf("Bye!! My ID is %d, my parent ID is %d.\n",getpid(), getppid());

return 0;

}

- Print its own PID and its parents PID

davidkebo@linux:~/code/week4/forks$ ./a.out

Hello!! My ID is 75189, my parent ID is 74907.

Bye!! My ID is 75189, my parent ID is 74907.

Bye!! My ID is 75190, my parent ID is 75189.

- If the parent exits, the forked child parent's ID would be 1 (init/systemd)

/CSCE-313/Lecture/Visual%20Aids/Pasted%20image%2020260206143704.png)

Notes

- What will happen to the child? only the parent is able to read the status code of the child

Every process must be "reaped" in Unix, otherwise it becomes a zombie and its task_Struct (a Linux kernel structure) hands around, which is wasted kernel space

Reaping: need to retrieve the status of a process

A process can be reaped only by its parent! So what happens when a process parent dies. Who reaps it?

Answer: init/systemd

The init process:

- The first process is

init/systemd(PID = 1) - Everything else is a child of this process

- When a parent of a process exits, its children become branches of

init - One of its benefits is to be able to adopt forgotten children

- Can you kill

init?- Yes, it runs as root so you can totally kill it, this will shut down your computer.

Process synchronization - I

The waitpid function makes a process wait for a child process.

pid_t waitpid(pid_t pid, int *status, int options)

The three arguments are:

- The target process's ID (many values interpreted differently!) [-1 => any child]

- The address of an integer where termination information (i.e., exit code) can be placed. You can pass NULL if you don't need the child's status.

- It's not necessary that the child exited.

- A collection of bitwise-or'ed flags. Use 0 to block until the target's termination.

A simpler way to wait for any child process is to use wait

pid_t wait(int *status) = waitpid(-1, \&wstatus, 0);

- This function waits until any of the child processes finish.

- Good with many children, and you want to wait for them in the order they finish.

- Your parent does a fork, then it waits the child, then it returns.

Notes:

- You can find out if the child exits or if it was killed by a signal and which signal.

- Blocks you until your child exits

- A shorter version is

wait, in this case you wait for any of your children- Useful when you know that you have only spawned one child

Process synchronization: example 1

int value = 5;

int pid = fork();

if (!pid) {

value += 5;

cout << "Child has value=" << value << endl;

} else {

value += 10;

cout << "Parent has value=" << value << endl;

}

prompt> ./a.out

Parent has value=?

Child has value=?

- What will the output be? Try it yourself!

int value = 5, status;

int pid = fork();

if (!pid){

value += 5;

cout<< "Child has value="<<value<kend";

exit(100); // trying to tell something to the parent

}else{

waitpid (pid, &status, 0); // wait for the child (parent listening)

value += 10;

cout << "Child terminated, status="

<<WEXITSTATUS(status) << endl;

cout<< "Parent has value="<<value<<endl;

}

prompt> ./a.out

Child has value=?

Child terminated, status=?

Parent has value=?

Notes:

- What is going to be on

&status? statusencodes not just the fact that the child exited with an status code, but also if in case it was killed by a signal, it gets encoded here also.- In this example you expect:

Child terminated, status=100 - How it gets encoded varies across different flavors of UNIX

- Here it returns an

int

- Here it returns an

Process synchronization: example 1

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

void wait_demo() {

int child_status;

if (fork() == 0) {

printf("HC: hello from child\n");

} else {

printf("HP: hello from parent\n");

wait(&child_status);

printf("CT: child has terminated\n");

}

printf("Bye\n");

}

Notes:

- The parent wants to synchronize with a child

- After the fork, the parent executes first, but then the parent is blocked (waits for the child to finish)

- The child executes, prints, exits and once it prints "Bye" the parent can continue execution and also print "Bye"

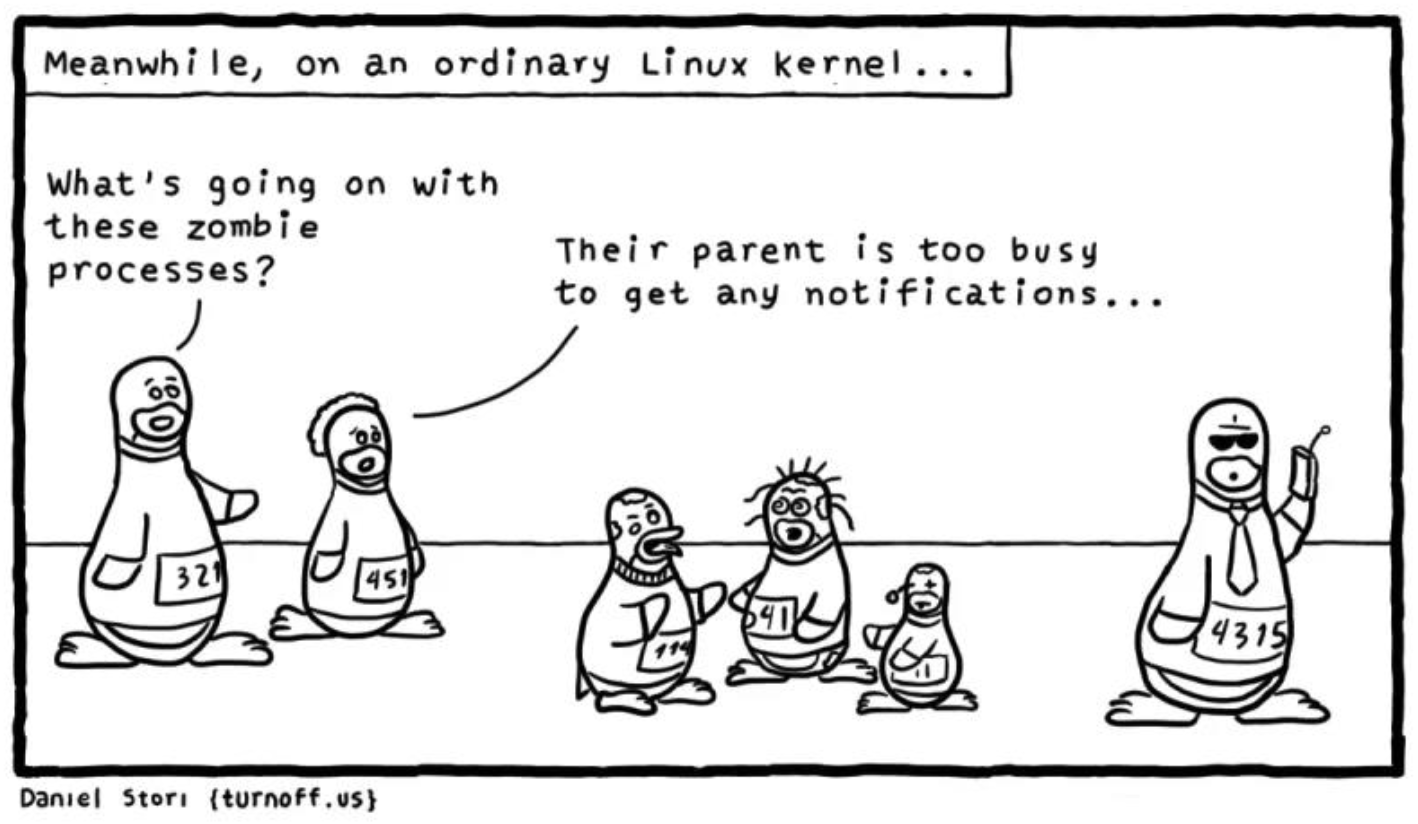

Zombie processes

- After a

fork()the child process executes independently of the parent. - If the parent does not wait for the child to terminate and executes subsequent tasks, then at the termination of the child, the exit status is not captured by the parent.

- A PCB (Process Control Block) entry remains in the process table even after the termination of the child.

- The orphaned child becomes a zombie process.

- Multiple zombies can result in memory leaks, because the PCBs consume memory and are not deallocated.

Notes:

- Zombies = Processes that hang around until they are adopted

- Processes can only be read by their parent

- The PCB entry in the kernel occupies real physical memory, this is the thing that actually takes up space, not the virtual memory space.

- It is actually the parent that makes the call to the children, it does not receive notifications from them.

Zombie processes: example 1

- Multiple zombie processes in the OS are harmful because

- The OS has one process table of finite size, so lots of zombie processes will result in a full process table.

Example: the fork bomb

A program creates infinite zombie processes because the parent does not wait for the child process.

#include <unistd.h>

int main()

{

while(1)

fork();

return 0;

}

Zombie processes: example 2

int main() {

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

for (int i=0; i<20; i++)

printf("I am Child\n");

} else {

printf("I am Parent\n");

while(1);

}

}

- Child: prints "I am child" 20 times and then exits

- Parent: too busy (doe snot wait for child)

davidkebo@linux:~/code/week4/zombie\$ gcc zombie1.c

davidkebo@linux:~/code/week4/zombie\$ ./a.out

I am Parent

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

[a.out]is the child. It is marked as<defunct>(this indicates the process is a Zombie)- You will see that the virtual size and the residence set size space values are 0

- A zombie process is not consuming resources but it is consuming a slot in the processor's pipeline, which is real memory.

Notes:

- Note Zombie process only exists if the parent is still running but does not read the children. If the parent gets killed or exits, the children will be adopted by

init.

Zombie prevention methods

How to prevent zombie processes?

a) Using the wait() system call

- Explicit reaping

b) Ignoring the SIGCHLD signal - An indirect way of specifying not to create zombies

c) Using a signal handler - Reap within the handler

Notes:

- Signal is an asynchronous method to communicate with a child.

- If you ignore

SIGCHILD, this means you do not care for your children to exit, so it won't create zombies. - A signal handler:

- You can register a callback associated with a specific signal

- Example: You register callbacks agains button precess, etc.

- Register a function with a signal, and every time a signal of that kind is generated, that function that you registered for that signal is going to get executed.

- It is something the OS sends to a process (a callback)

Zombie prevention using wait()

- When the parent process calls

wait()after the creation of a child, it waits for the child to finish, and reaps the exit status of the child. - The parent process is suspended until the child has terminated.

- While waiting, the parent

does nothing else.

int main() {

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

for (int i=0; i<20; i++)

printf("I am Child\n");

} else {

wait(NULL); // NEW LINE

printf("I am Parent\n");

while(1);

}

}

- What is the purpose of

while(1)?- An infinite loop so that the child does not end, basically waiting for the parent to call

waiton it.

- An infinite loop so that the child does not end, basically waiting for the parent to call

davidkebo@linux:~/code/week4/zombie\$ gcc zombie1.c

davidkebo@linux:~/code/week4/zombie\$ ./a.out

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Child

I am Parent

davidkebo@linux:~$ ps aux | grep a.out

davidke+ 78835 99.4 0.0 2496 576 pts/4 R+ 17:40 0:13 ./a.out

davidke+ 78836 0.0 0.0 0 0 pts/4 Z+ 17:40 0:00 [a.out] <defunct>

davidke+ 78880 0.0 0.0 8168 2568 pts/5 S+ 17:41 0:00 grep --color=auto a.out

Zombie prevention methods

How to prevent zombie processes?

- a) Using the

wait()system call- Explicit reaping

- b) Ignoring the

SIGCHLDsignal- An indirect way of specifying not to create zombies

- c) Using a signal handler

- Reap within the handler

Notes:

- Every time a child process dies, its parent receives the signal

SIGCHILD - If you explicitly ignore the

SIGCHLDsignal, then the OS interpret this as that you are not interested in your children so it won't keep the zombie process

Zombie prevention using wait()

- When the parent process calls

wait()after the creation of a child, it waits for the child to finish, and reaps the exit status of the child. - The parent process is suspended until the child has terminated.

- While waiting, the parent does nothing else.

int main() {

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

for (int i=0; i<20; i++)

printf("I a m Child\n");

}else {

wait(NULL);

printf("I am Parent\n");

while(1);

}

}

Zombie prevention using SIGCHLD & SIG_IGN I

- When a child is terminated, a corresponding

SIGCHLDsignal is delivered to the parent. - Upon calling

signal(SIGCHLD, SIG_IGN), theSIGCHLDsignal is ignored by the system. - The child process entry is deleted from the process table and no zombie is created.

int main() {

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

for (int i=0; i<20; i++)

printf("l am Child\n");

} else {

signal(SIGCHLD, SIG_IGN);

printf("I am Parent\n");

while(1);

}

}

- We are registering a callback with the

SIGCHLDsignal- Basically we are just saying: "ignore that signal"

- Note you can also put this line at the start of the program

- Why you would ever need Zombie processes?

- When you do not want your child to disappear in case it exits first than the parent

- This guarantees that you can find out about how your children exited

- Even though the parent is in an infinite loop, having done the callback to ignore

SIGCHLD, the child does not become zombie.

Zombie prevention using SIGCHLD II

- The parent process installs a signal handler for the

SIGCHLDsignal.- The signal handler calls

wait()system call within it. - When the child terminates, the

SIGCHLDis delivered to the parent. - On receipt of

SIGCHLD, the corresponding handler is activated, which in turn calls thewait()system call. - The parent collects the exit status almost immediately and the child entry in the process table is cleared.

- The signal handler calls

void func(int signum) {

wait(NULL);

}

int main() {

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

for (int i=0; i<20; i++)

printf("I am Child\n");

} else {

signal(SIGCHLD, func);

printf("I am Parent\n");

while(1);

}

}

- When our child terminates, and the OS calls your handler, then this handler automatically calls

wait()on it.

Killing zombie processes

The state of a terminated child when the parent is still running w/o calling wait()

int main () {

if (fork()){ // parent

while (true){//infinite loop

sleep (1);

}

}else{// child

cout<<"Child about to exit"<<endl;

}

}

/CSCE-313/Lecture/Visual%20Aids/Pasted%20image%2020260211142841.png)

- Even if you manually try to kill a zombie, it still won't die, only a

wait()can kill it.

Who reaps a child when the parent is killed?

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <signal.h>

int main() {

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

printf("parent pid = %d.\n", getpid());

pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

printf("child pid = %d.\n", getpid());

pause();

} else {

pause();

}

} else {

printf("grandparent pid = %d.\n", getpid());

pause();

}

// grandparent

return 0;

}

Notes:

init, the parent process of everything, is basically in a loop that just keeps callingwait()on zombie processes.