M7 - Expert Witness

Class: CYBR-405

Notes:

The Expert Witness

The Expert Witness

An expert witness is generally defined as a person who possesses specialized knowledge, training, education, skills, and/or experience that goes beyond that of ordinary members of the general public. State and federal courts allow expert witnesses to testify in lawsuits or criminal defense cases in order to assist the decision makers (usually the jury or judge) so they can determine how to rule on a case.

Responsibilities of the Expert Witness

The responsibilities of the expert witness are to explain and provide facts about particularly complex issues that are beyond the average knowledge of the general population. An effective expert witness can take complex technical terms and explain them in a way that typical jurors can understand. The jurors can then take that information and use it to help them understand parts of the case. The jurors will then be better equipped to render an informed verdict.

In addition to presenting simplified versions of complex issues, an expert witness also assists the attorney's understanding of relevant facts that they might not be familiar with. The expert witness educates the attorneys so they are armed with knowledge of a particular industry relevant to their case.

Expert witnesses are also used to help attorneys evaluate a potential case. In the event the expert witness had knowledge of a computer hacking incident with numerous data breaches that have occurred across the cyber spectrum, the expert witness would help determine whether or not the potential victim had complied with data security policies and procedures and if that fact contributed to any potential liability on the part of the potential client(s).

Testimony of the Expert Witness

The testimony of the expert witness should conform to all court and professional standards for testimony and should conform to the widely applied Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) and Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP). These rules ensure that the expert witness acts as an agent of the legal system, has a character known to be honest and ethical so the report can be taken into evidence as truthful and acts as an objective individual who can present an opinion based upon facts.

Role of the Forensic Expert as an Expert Witness

In any civil or criminal case, the attorneys involved in the litigation may choose to hire any number of experts to ensure that each fact is scrutinized and validated. From these efforts, an expert may be hired but may not produce a result that supports the objective of the attorney. However, recognize that the objective of the attorney is never the objective of the forensic investigator.

The job of the forensic expert witness is to report the forensic processes used to collect evidence, the evidence collected, the events leading to the investigation, the events that occurred during the investigation, and any reasonable conclusions from the facts of the investigation.

Duties of the Forensic Expert

A forensic expert can begin working as early as the first steps in investigating a case. This enables a forensic expert to testify of his or her first-hand knowledge of the processes, events, evidence, and conclusion in the case.

The forensic expert may also perform the following duties:

- Review the evidence.

- Review the processes that collected the evidence.

- Review the tools that analyzed the evidence.

- Review the theories of both attorneys for the case.

- Review the conclusions of all other forensics investigators.

- Review the notes, journals, and other written communication that pertain to the case.

The Forensic Expert as a Witness

In cases where the forensic expert is called to be a witness, they must testify in court by answering questions. This process of providing testimony begins by swearing in the expert. In the swearing-in process, the expert acknowledges that they are under oath and will tell the truth.

After this step, the expert begins answering the attorneys' questions concerning the case. The questions asked by the attorney who hired the expert are called examination, while the questions of the opposing attorney are called cross-examination.

The attorneys and the court fully expect the truth from everyone who provides testimony; this particularly includes forensics experts who should be familiar with the legal system, comfortable in a courtroom, and be objective (i.e., neutral) to the outcome of the case. The expectation is so severe that not meeting the expectation of truth has been criminalized. This crime is called perjury and can bear severe personal and professional punishment to the expert, as well as damage the case of the expert's employer.

Responsibilities of Expert Witnesses During Testimony

In court, the big-picture presentation is the responsibility of the attorneys. Each attorney will call their expert witnesses to prove the facts of their theory or to disprove the facts of the opposing attorney's theory. The responsibility of the forensic expert/witness is to answer questions about the theory and present the evidence in such a way that everyone who hears the presentation will:

- Understand the evidence's contribution to proving a theory of events.

- Understand the evidence's contribution to disproving the opposing attorney's theory.

- Understand the evidence's validity (precision of evidence, accuracy of the tests, and qualifications of the forensics investigators, etc.).

- Understand the qualifications of the person presenting.

An expert witness's evaluation of quality is tightly coupled with the history of professional conduct and the credibility of

the forensic expert.

Discovery

In general, the court will provide the evidence to the expert witness upon request as part of a discovery phase. Anything that is written on paper or written electronically is subject to discovery. Discovery describes the effort put forth to collect information about a case. Discovery can require that information be turned over to the attorney. The information can be conveyed in one or more forms, including:

-Paper or electronic documents.

- Processes or procedures used by other forensic persons to collect the evidence.

- Answers to questions supplied under oath to the court.

- Examination of the scene and evidence.

- Written requests for admission of a fact.

- Written reports to detectives, forensics team leaders or management, and attorneys.

- Any final written reports.

Reviewing the Facts of the Case

After the expert witness supplies the result, the attorneys will review the facts of the case and assess:

- Whether the facts of the report help or hurt the current case.

- Whether the facts of the report can be damaging to the attorney's client.

Consultation Between Experts and Attorneys

The attorneys may also consult the expert to assess whether or not a jury could understand and believe the facts of the report. The attorney's role is always to convince a judge or jury of what could have happened using facts. In many ways, the role of the attorney is less about the truth and more about convincing a judge or jury. Therefore, an attorney will certainly consult the expert for advice on the following:

- The attorney's and expert's capability of instilling confidence about the evidence, process, and investigators to a judge or jury.

- The expert's reputation and skill compared to the opposing attorney's expert's reputation and skill.

- The attorney's and expert's capability of conveying the facts supported by the evidence.

- The attorney's and expert's capability of conveying any reasonable conclusions supported by the facts in the case.

Possible Outcomes of Consultation Between Experts and Attorneys

After the expert and the attorney collaborate on the investigative results, the attorneys can choose to take any number of actions, including:

- Ignore the report.

- Seek an expert who is better at analyzing evidence or presenting evidence in a question/answer session in court.

- Accept the testimony of the expert before a judge and jury.

- Seek an agreement with the court and other attorneys to affirm that key facts stated in the forensic report are indeed facts.

Presenting Evidence and Questioning

Importance of a Convincing Presentation of Evidence

Litigation can involve more than just the evidence. Litigation can involve a deep evaluation of the messenger. In many scenarios, the evidence is equally as important as the presentation. In court, the attorney who wins the case frequently has the best presented theory, but not necessarily the theory supported by the best evidence.

In essence, the best evidence is not necessarily the evidence, facts, and conclusions that are more precise or accurate. The best evidence is often the evidence that is most believable and convincing to a judge and/or jury.

It is never the job of the forensic investigator/reporter to produce the theory. Rather, the law enforcement officials and/or attorneys involved in a particular civil or criminal case produce the theory. The job of the forensics investigator/reporter is limited to only answering questions about the case. As a result, the answers presented to the court must be convincing.

Planning Witness Examinations

The witness examination is the phase of the trial in which attorneys ask questions and expect answers. In the context of digital forensics, the questions are related to digital equipment and computers. The answers are the product of the work and experience of the digital forensic professional.

The goal of both direct and cross-examination is identical. With both, the attorney uses questions to support their theory of events or facts, while excluding other theories (such as those put forth by other attorneys in the litigation). It is to the advantage of the attorney to tell the theory or story quickly or

Scenario else lose the attention of the audience (judge and jury), which could cause important facts to be missed by that audience. It goes to say that providing too much information or too much detail might unnecessarily distract the decision-makers in the case. The attorney is also benefited by pausing the story periodically to support the facts of their story with evidence.

Scenario:

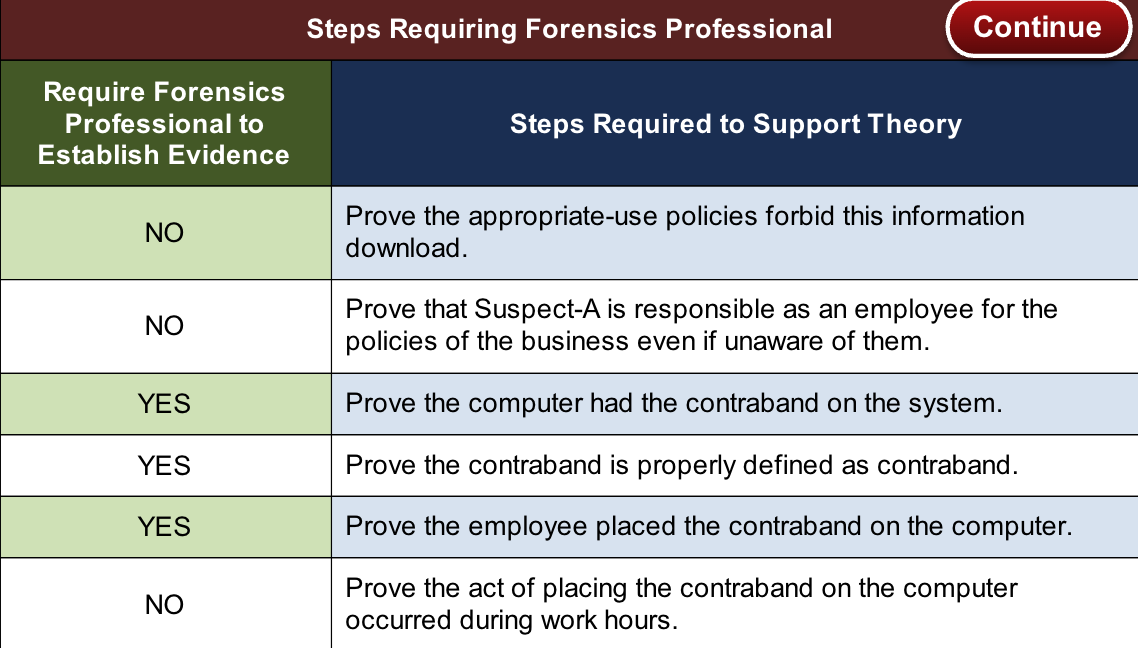

Suspect-A has been caught with contraband material on his business computer. The computer is a laptop that the business allows employees to take home. The contraband is essentially legal for personal use, but the appropriate-use policies forbid personal downloads on business assets. Suspect-A states that he did not download the contraband and that he is unaware of any policy that prohibited the download. Forensic examination later proves that the download occurred from the office during a time when the employee was known to be at work. The suspect is fired as a result of the evidence. Later, the suspect sues the business claiming wrongful termination.

An example direct examination plan for this scenario would attempt to build a case that excluded all other possibilities. This table identifies the steps in the investigation requiring a forensic professional to establish evidence.

Questioning Overview

The more evidence that can be produced, the more likely the audience or jury will believe the story. In fact, the story had better be believable or else it will be rejected regardless of the evidence. A good storyteller or witness will have a believable, reasonable, and clear story to tell that is long enough to cover the essential facts but short enough not to detract from the story.

Accomplishing the goal of the examination requires planning. The storyteller had best know where the story is going to end before introducing characters and developing the plot. If the storyteller fails to understand the goal, convincing a judge or jury of the accuracy of a theory will be difficult and tiring. The story must be told clearly without any side stories, extra plot threads, extra characters, or irrelevant events.

Though similar in goal, direct and cross-examination plans are developed differently. In planning for direct examination, the attorney and their hired forensic professionals will work together to produce the correct questions in the correct order. It is the attorney's responsibility to win the case and accomplish the goals of the litigation, whether the goal involves a civil suit, or to prosecute or defend a criminal.

Direct and Cross-Examination

The job of the forensic professional is to answer questions. After direct-examination is complete, the opposing attorney will begin cross-examination. The objective of cross-examination is to cast a shadow of doubt. In general, this shadow is best cast by proving an alternative theory.

Since producing and proving an alternative theory is not possible in some cases, the second-best action to take in cross-examination is to attack the following:

- Theory presented by the opposing attorney.

- Evidence presented to support the theory.

- Procedures used to collect/analyze the evidence.

- The person who collected/analyzed the evidence.

- The person presenting the evidence.

Direct-Examination

The questions asked by the attorney who hired the expert.

Cross-Examination

The questions asked by the opposing attorney or the attorney who did not hire the expert.

Questioning and Cross-Examination

As an employee of the attorney and an expert on digital forensics, the digital forensic expert should cooperate with the attorney to ensure that the best questions are asked. Feedback from the attorney regarding the details of the investigation may also feed forward into a written forensic report that is provided as evidence to a court.

The attorney to perform the cross-examination will also plan a set of questions to ask the forensics professional. These questions are designed to undermine the ideas put forth by direct-examination, support an alternative theory, and cast a shadow on the contribution of the evidence. The questions of direct-examination do not need to exhaust all possibilities for error. The forensics professional may provide opinions or conclusions without first providing facts to support those opinions. It may be that these facts will be explored further under cross-examination. The attorney should ask questions that support the case.

Providing Quality Answers

For the forensics expert witness, the importance is on quality answers, not quality questions. Quality answers always address the unknown in the question by providing needed evidence to support rational, justifiable conclusions. The task of answering questions is very challenging because what seems to answer the question in one's mind may be off target in reality. What makes one answer better than another?

- Clear

- Ability of the decision-makers to clearly understand your answer.

- Accurate

- All facts must be correct. All conclusions are sound and supported by evidence.

- Precise

- Answer must identify evidence exactly.

- Precise

- Answer must identify evidence exactly.

- Thorough

- Answer must address every aspect of the question.

- Thorough

- Answer must address every aspect of the question.

- Rational

- Answer must engage audience (judge and jury) and be believable.

- Objective

- Forensic professionals must show no bias toward a particular outcome in the case.

Types of Questions Asked of Forensic Professionals

Let's look at some examples of the types and kinds of questions that may be asked of forensics professionals.

Attack the Evidence: #1

Question: Could another person have used suspect-A's computer to download porn movies without suspect-A's knowledge?

Aim: To cast a shadow of doubt on the theory by getting the forensic professional to admit that another person could have downloaded porn. Notice how the question provides no details about a particular instance in which porn was downloaded.

Answer: There is no reasonable scenario in which porn could have been downloaded on the dates in question to suspect-A's computer without suspect-A's knowledge of and commission in the act.

Attack the Evidence: #2

Question: What standard did you use to assess whether the movie downloaded was pornographic?

Aim: To cast a shadow on the illicit nature of the evidence. If the evidence was not provably pornographic in nature, then how could suspect-A have known it was wrong to download it?

Answer: Though the movie itself is unrated, the movie was downloaded from a website that specialized exclusively in pay-per-download pornographic media. The website's business is documented in its own "terms of use," as noted in the evidence report.

Attack the Evidence: #3

Question: Did you examine the disk for worms or viruses that could have downloaded the pornography automatically and without suspect-A's knowledge?

Aim: To cast a shadow on the evidence by suggesting that not all evidence was considered. In addition, this question attacks the competency of the person collecting the evidence.

Answer: The disk was fully scanned for any known worms or viruses, and none were found.

Attack the Evidence: #3 (Follow-up)

Question: You say "known." Hypothetically, could there be an unknown worm or virus that would download this pornographic movie?

Answer: No, the website requires a username and password prior to downloading. Further, the computer is equipped with a modern and updated firewall/antivirus suite which would prevent such. No unusual activity was detected by these tools.

Attack the Procedures

Question: You analyzed the web cache using a Helix CD? Would it not have been better to use Encase instead?

Aim: To discredit the result of the analysis by suggesting that the person performing the analysis did not use the best tools available.

Answer: Both the Helix CD and Encase provide equivocal results.

Attack the People

Question: Do you believe that suspect-A committed this crime? Surely you must have an opinion?

Aim: To demonstrate a bias in the forensic professional reporting the results of the investigation.

Answer: It is my job to be objective and neutral. I have no interest in the suspect beyond the questions posed to me by the court regarding the evidence.

Note: Other strategies for "attacking the people" involve trying to make them lose their temper, proving unprofessionalism, discrediting their qualifications, and causing them to appear unsure of their answers. The correct response is always to answer the questions with all the characteristics described previously.

Avoiding Traps During Questioning

These questions have highlighted a basic strategy common to question-askin by attorneys in cross-examination: suggest a hypothetical scenario to discredi the theory, evidence, procedures, and/or people in the case. The theory is pu forth in hopes that the jury understands or believes the hypothetical scenario is truer and more accurate than the scenario presented under direct examination

It is critical that forensic professionals not step into the traps set by attorneys under cross-examination. While all answers should maintain the characteristic of good answers, forensic professionals should not allow their objectivity and professionalism to be compromised by allowing attorneys to present hypothetical situations as fact.

In addition to highlighting the basic strategy of attorneys in cross-examination, our examples also highlight a good strategy for avoiding those dangers. The strategy is simple: think before speaking and provide professional answers that bear all the qualifications of quality answers, but also appropriately emphasize the hypothetical nature of the question.

Tipping the Scales

To restate, the objective of forensics is to answer questions for the legal system. This objective is partially accomplished by gathering and analyzing evidence. After the evidence is collected, it must be reported. As noted earlier, the evidence is often reported informally throughout the investigation, during the evidence collection and analysis phase, and formally to a court or governing body once the collection and analysis is complete.

The collection and analysis of the evidence is only part of the overall effort. The evidence must be convincing to a judge or jury. It has already been shown that the impression and qualifications of the expert witness play a tremendous role in the ultimate acceptance of the evidence. However, both attorneys in a particular litigation (whether civil or criminal) can produce their own expert witnesses.

A good expert witness for one attorney can be countered by a better expert witness for the other attorney. In the end, a good expert witness can tip

the scales and make the overall difference in a case.

Presentation of Evidence Outside the Courtroom

Up to this point, this discussion has largely centered on the oral presentation of evidence by an expert witness to a judge or jury in court. Not all presentations are made in court. In fact, many presentations of evidence are made to attorneys, detectives, and business leaders prior to legal actions being considered. These early presentations answer questions such as, "Can the case be convincingly proven in court?," or "Is the litigation likely to be successful?"

Even if the setting is not a legal setting, the theme of these answers remains true to the objective of forensics: answer questions for the legal system. And even if the setting is not a courtroom, the evidence of the case is presented by an expert witness who is subject to the prior detailed expectations.

Credibility of the Expert Witness

Credibility of the Expert Witness

The credibility of an expert witness begins with the professional conduct of the expert. The credibility continues to be built by demonstrating professional conduct on a specific case. The expert witness must be on guard at all times during an investigation and must demonstrate the following when reporting results:

- Did not arrive at conclusions before all reasonable leads had been exhausted.

- Conclusions put forth are unbiased (i.e., supported by the evidence).

- Details of the case were kept confidential.

- Is current with conventional computer hardware, software, networking, and forensic tools.

- Correctly reported important milestones in the case.

NOTE: The forensic investigator should always maintain a journal documenting the dates and important facts from the investigation. These facts should be reviewed regularly while testifying in court or otherwise producing oral/written reports. Keep in mind these types of notes could be a part of the discovery process.

History of Professional Conduct

The behavior of the expert witness outside the profession of forensics is equally important to the behavior of the expert inside the profession.

So, the actions or behavior of a person both on and off the job impact the professional conduct evaluation.

On-the-Job Conduct

- Compliance with ethics standards for law enforcement, forensic investigations, and other professional organizations.

- Standards of behavior set by the expert's employer or commonly accepted as characteristic of the expert's field.

- Integrity.

- Expertise and technical knowledge.

- Objectivity.

- Confidentiality.

- Compliance with standards for forensic investigations.

Off-the-Job Conduct

- Compliance with ethical standards for average citizens. For example, an expert who routinely shows disregard for public speed laws may be considered unprofessional.

- The nature of the expert's morals. For example, an expert whose moral beliefs and training support socially unacceptable behavior such as polygamy, pornography, and lewd conduct may be considered unprofessional.

- Compliance with law and regulations for average citizens. For example, it is not difficult to assume that an expert who compromises his integrity by lying in civil court regarding a private lawsuit with a neighbor will have no problem lying in court regarding other matters.

- Inappropriate comments posted to social media or web blogs. Any posts to social media or web blogs can be (and are routinely) queried by opposing counsel in order to confront the forensic expert during testimony if such information shows the expert is unprofessional or holds a bias for or against an issue or party to the case.

Case Closed

Factors That Influence the Outcome of Cases

In addition to a good expert witness, other factors that can strongly influence the outcome of a particular case include:

- Attorneys

- Theories of Attorneys

- Prior records of defendants

- Acceptability of the evidence

- Other facts outside of those produced by forensic analysis

These additional influences can negatively impact even clear and neutral evidence presented by an articulate and charismatic expert witness. With these additional influences, the expert witness may have a difficult time convincing a judge or jury of a particular set of facts or events. While these factors are often outside of the control of the expert witness, the negative repercussions can be countered by quality forensic reports.

The contents of the report are critically important. A simple mistake in the reporting of evidence can mean life or death for a man accused of murder. It can also mean millions of dollars for a man accused of a cyber-crime.

From Investigation to Case Closed

In the ideal case, the investigation will be short and the criminal apprehended quickly. However, many cases fall short of ideal and require years to resolve. Therefore, a gap is formed between the time the report was written and the time the case is resolved. During the gap of time from when the evidence is collected and when a case is resolved, several key items may change.

- The detective and/or forensic investigator may no longer be available.

- The procedures used to analyze the data may have been validated or invalidated in court.

- The evidence itself may reveal new information that was not possible during its first analysis.

- The capability to review evidence may have deteriorated as technology to read certain data formats disappears.

- The evidence may deteriorate beyond a point at which any access to the original evidence sources is possible (entropy).

- The report may need to be modified to suit new standards for reporting, or standards for evidence analysis.

Post-Mortem Activities

These factors can work to sabotage the effectiveness of forensic reports and expert witness testimony. The context of these factors is public or criminal in nature, but the same issues remain for civil cases as well. These components present an interesting problem for the forensic professional:

Given the time between the investigation and conclusion of trials, how can the investigator help combat these factors in the future?

Probably the single most viable solution to counter the possible gap between the investigation and the trial is to hold a post-mortem session with the attorneys of the case to inquire about what would have made the case stronger, and how the report could have been improved.

What is a Post-Mortem Session

This post-mortem session is the only oral examination in which the attorney is receiving the questions asked by the forensic investigator. The questions can be asked in written form through a survey, but a face-toface meeting is generally better and more effective.

Reviewing, re-analyzing, and eventually presenting written/oral testimony about the forensic work of another person helps a forensic professional learn from the mistakes of others.

Since digital forensics is a relatively new field, this session is critical to building and establishing skills and experience. The relative youth of the digital forensics field and the volume of new digital forensics investigations today suggest that only a relatively few cases will involve the work of others. When they do occur, learn from them.

In much the same way that reviewing, re-analyzing, and presenting the work of others will provide experience, doing the same for one's own work is even more valuable. Most forensics investigators will have a career that provides enough time to see many cases to closure. Even if the experience of postmortem sessions is limited to very few investigations, the experience is invaluable.

Basic Questions for Post-Mortem Sessions

The attorney's time (as well as your time) is quite valuable and should not be wasted with frivolous questions. Allocate ample time to answer every question well but be careful that you do not over-extend your stay. The following are some of the basic questions that can help build a positive experience through the post-mortem sessions.

- What problems did the opposing attorneys discover about the written report? My oral testimony?

- Were my answers clear, accurate, and precise?

- Were my answers clear, accurate, and precise?

- Did I appear to be an objective, neutral third party?

- What was your impression of me during the deposition?

- Did that impression change when you questioned me in court?

- How can I cast a better image as an "expert" in the field of digital forensics?

- In your opinion, was my testimony convincing to the judge and jury? How about the written report?

Documenting the Post-Mortem Session

It is best to electronically or digitally record the conversation and write the answers down later, or simply write short notes about the answers provided. Remember, time is important, and taking long notes disrupts the flow of the meeting. Be careful not to ask too many questions of the attorney. If there are too many questions, the attorney may never permit another post-mortem session with you.

Finally, take the answers provided by the attorney and learn. The experience of one civil trial or one criminal trial can be invaluable in the next investigation. This closes the loop between forensic investigators and forensic reporters as the duties of the forensics reporter provide ample opportunity to learn how to better perform the duties of the forensic investigator. After many successful iterations through this loop, the forensics professional should be both a successful investigator and a successful reporter of digital forensics.