04 - Process API - Part I

Outline

- What is exec()?

- The exec family of functions

- fork() and exec()

What is exec()?

The Process API

Common process operations available in Operating Systems

- Create

- When we type a command into the shell, or double-click on an application icon, the OS is invoked to create a new process to run the program you have indicated.

- Destroy

- Most programs terminate once they complete, but provision for terminating a runaway process is available.

- Reap

- Best example is the shell within which other program(s) can be invoked.

- Control

- Other operations besides the ones above (e.g., suspend, resume, etc.)

- Status

- Check on status of process (e.g., runtime, memory, priority, state, etc.)

Notes:

-

When a process exits, it doesn't fully exist right away, it waits for someone to retrieve its process status (did you exit normally, did you get killed by a signal? etc.)

- A process never really finished until it has been read

-

If you look at the man page of

execve(page 2)- the way that you create a new process is by making a process of yourself, and then exec'ing

-

When you return from main, you return to your caller, and the caller exists for you, this is the only way

Example: Run this in a terminal

less .usr/share/dict/words

Find PID of a process

ps -u

From another terminal you can sen a kill signal to the process running:

kill -SIGKILL 83358

- Saying "kill yourself"

- Done with

kill SIGKILL - That number is the PID of the process we want to send to the background

To suspend the process (send it to the background):

kill -TSTP 83358

Send a STOP signal:

kill -STOP 83358

- This will basically just stop the process

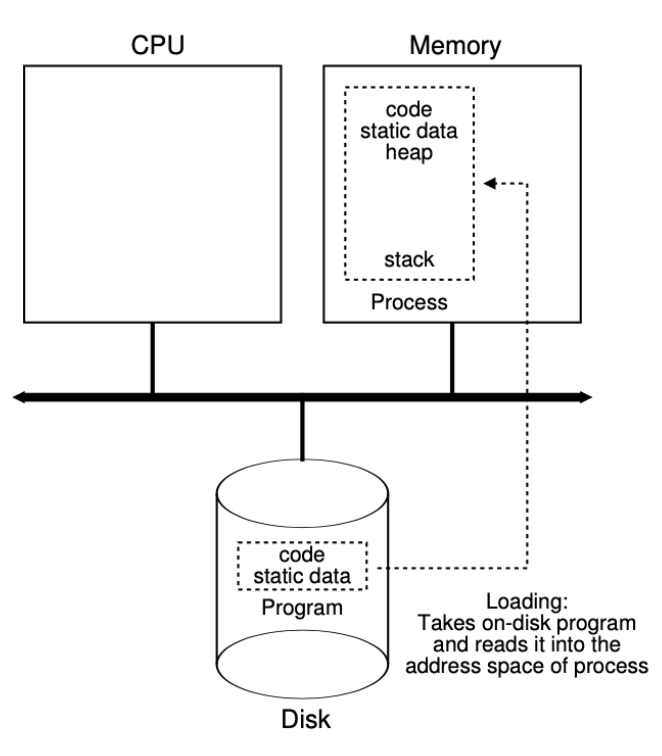

From Program to Process

Notes:

- The way you turn a program (some bits on disk) into a process is through

execexecwill read these bits and start executing them

- The caller that calls

exec, it remains the same (same PID and virtual address space), what has changes is that in your address space it has loaded bits from the program

Process API

A process can run more than one program. The currently running process can ask that the OS load a different program into the same process.

The new program inherits some process state, such as current directory, open file handles, privileges etc.

This is done at the system level, with only four syscalls:

fork()exec()—Altered carbon on Netflix!wait()exit()

Notes:

- You may want to know wether one of your child processes has been finished, you can either

wait()for it or look at the status information of it...?

Running another program from a C/C++ program

- Assuming the other program's name is name.

- The current program makes a system call

execXX("name", arglist). - The kernel loads the "name" executable program from the disk into the process.

- The kernel copies arglist into the process.

- The kernel calls

main(arglist)of the "name" program.

int main () {

char *args[] = { "ls", "-l", "-a", NULL };

printf ("=====BEFORE========\n");

execvp (args[0], args);

printf ("======AFTER========\n");

}

- '

v' inexecvpindicates that arguments will be in the form of a vector (array)

davidkebo@linux:~/code/week4/exec\$ ./a.out

=====BEFORE=======

total 32

drwxrwxr-x 2 davidkebo davidkebo 4096 Sep 12 04:25.

drwxrwxr-x 6 davidkebo davidkebo 4096 Sep 12 04:13 ..

-rwxrwxr-x 1 davidkebo davidkebo 17416 Sep 12 04:25 a.out

-rw-rw-r-- 1 davidkebo davidkebo 279 Sep 12 04:25 exec1.cpp

- Note the

AFTERprint is cut out because of theexec execsucceeds, so you get replaced by "`ls"- You don't come back after termination

Notes:

- How does it actually give you the listing of the current directory?

- In this case it is

ls, but exec looks the path oflsin the caller's path first. - The first argument is the name of the program itself, the arguments that is getting is in vector form (need to end in a nullptr to indicate end of vector)

- You are constructing an array where the first pointer pints to "

ls", the second, "-l", the third, "-a", and the last one is always NULL- exec tries to find the first executable "

ls", if there is one, it will take it.

- exec tries to find the first executable "

What happens in exec()

Initial state of memory before hitting line: execvp("ls")

/CSCE-313/Lecture/Visual%20Aids/Pasted%20image%2020260206135125.png)

- a.out is a compiled program, the OS mapped the bits of this executable somewhere in memory

- Following instructions on a.out will cease to exist in memory, therefore are not executed

/CSCE-313/Lecture/Visual%20Aids/Pasted%20image%2020260206135149.png)

- When a.out calls

execvpthe process address space for a.out gets completely replaced

Where is the second message?

- The

execsystem call clears out the binary of the current program from the current process and then in the now empty process puts the code of the program named in the exec call and then runs the new program - execvp does not return if it succeeds!

int main () {

char *args[] = { "ls", "-l", "-a", NULL };

printf ("=====BEFORE=======\n");

execvp (args[0], args);

printf ("======AFTER========\n");

}

davidkebo@linux:~/code/week4/exec$ ./a.out

=====BEFORE=======

total 32

drwxrwxr-x 2 davidkebo davidkebo 4096 Sep 12 04:25 .

drwxrwxr-x 6 davidkebo davidkebo 4096 Sep 12 04:13 ..

-rwxrwxr-x 1 davidkebo davidkebo 17416 Sep 12 04:25 a.out

-rw-rw-r-- 1 davidkebo davidkebo 279 Sep 12 04:25 exec1.cpp

Example: command interpreter I

Now we want to write our own shell, lets try it!

char command[MAX_COMMAND_LENGTH];

while (true) {

command = read_command(stdin);

if (command == "exit") break;

execvp(command,...);

}

- If you call exit, I will exit

- If you type something else, I will accept it and try to read the command

Caution: execvp() loads the executable for the new command into the process's memory. It therefore overwrites the executable for the command interpreter!

Notes:

- A shell is actually an ordinary program (it has normal privileges as many other processes)

- It basically reads a line of input and runs a command on it.

- What is wrong with this version of the shell?

- The thing here is that it gets replaced by

execvp()so the shell is gone

- The thing here is that it gets replaced by

Example: command interpreter II

char command[MAX_COMMAND_LENGTH];

while (true) {

command = read_command(stdin);

if (command == "exit") break;

if (fork() != 0) {

/* parent - go to loop */

...

} else {

/* child */

execvp (command, ...);

}

}

- Here

fork()andexec()enable co-existing processes. - However, we do not know the order of their execution since that is entirely left up to the OS.

- We are still missing the parent-child dependency that is typical of a command interpreter where the parent waits for the child to complete before proceeding further.

Notes:

- Now our shell reads a line of input and does a fork!

- If its the parent (process ID of the child) then runs loop

- The child is the one that runs the

exec'ing - There are two small problems with this version:

- If the parent comes back to the loop (does not know about the child), and reads/writes to the same file that the child is reading/writing that would be a mess

- The paren must wait for the child in order to avid this

- We do not want to compete on the standard input

- If the parent comes back to the loop (does not know about the child), and reads/writes to the same file that the child is reading/writing that would be a mess

Example: command interpreter (solved)

char command[MAX_COMMAND_LENGTH];

while (true) {

command = read_command(stdin);

if (command == "exit") break;

if ((pid = fork()) > 0) {

/* parent - run command in foreground, i.e., wait */

waitpid(pid, &status, 0);

} else {

/* child */

execvp(command, ...);

}

}

Notes:

- The standard input of the parent is the same as the standard input of the child

- Here, what the parent is doing is just waiting for the child to exit, for this, we use

waitpid - The status of the child will be placed in

status- If child exists with 0: status = 0

- If child exists with 1: status = 1

- If the parent did not do this, the children will run unsoundly

- The process will just hang up in the OS

- The only process that will be able to read the status of this process is its parent, that is why we implement a child wait

Exec family of functions

The exec functions execute a file. They replace the current process image with a new process image. Even though they are similar, there are differences between them, and each one of them receives different information as arguments.

int exedl ( const char *path, const char *arg, ... );

int execlp( const char *file, const char *arg, ... );

int execle( const char *path, const char *arg, ..., char *const envp[] );

int execv ( const char *path, char *const argv[] );

int execvp( const char *file, char *const argv[] );

int exeque( const char *path, char *const argv[], char *const envp[] );

The first three are of the form execl and accept a variable number of arguments. To use this function, we must include the <stdarg.h> header file.

The latter three are of the form execv in which case the arguments are passed using an array of (char *) where the last entry is NULL.

Differences among the seven exec functions

/CSCE-313/Lecture/Visual%20Aids/Pasted%20image%2020260206141913.png)

Relationship between the six exec functions

/CSCE-313/Lecture/Visual%20Aids/Pasted%20image%2020260206141950.png)

Notes:

execveis the real system call, the other calls are just packaging arguments to itenviron: When you create a child, you can actually see them from anywhere in the environment

Exec family of functions: execl()

execl() receives the location of the executable file as its first argument. The next arguments will be available to the file when it's executed. The last argument must be NULL.

int execl(const char *pathname, const char *arg,..., NULL)

#include <unistd.h>

int main(void) {

const char *file = "/usr/bin/echo";

const char *arg1 = "Hello world!";

execl(file, file, arg1, NULL);

return 0;

$ gcc execl.c -o execl

$ ./execl

Hello world!

Notes:

- Since there is no p, it expects the full path of the executable, and since there is no

v, it also expects all arguments in separate (not as an array)

Exec family of functions: execlp()

execlp() is similar to execl(). However, execlp() uses the PATH environment variable to look for the file. Therefore, the path to the executable file is not needed.

int execlp(const char *file, const char *arg,..., NULL)

#include <unistd.h>

int main(void) {

const char *file = "echo";

const char *arg1 = "Hello world!";

execlp(file, file, arg1, NULL);

return 0;

}

$ gcc execlp.c -o execlp

$ ./execlp

Hello world!

Notes:

- The program that you want to run, you just give it the simple name, and

execlpwill look it up in the path for you.

Exec family of functions: execle()

With execle(), we can pass environment variables to the function, and it will use them:

int execle(const char *path, const char *arg, ..., NULL, char *const envp[])

etrues to override the environment of the child, so that it can do something else- At the end, you give to the child its own environment, this is how we can influence the environment of the child

#include <unistd.h>

int main(void) {

const char *file = "/usr/bin/printenv";

const char *arg1 = "MAKEFILES";

const char *const env[] = {"MAKEFILES=foo", NULL};

execle(file, file, arg1, NULL, env);

return 0;

}

$ gcc execle2.c -o execle2

$ ./execle2

foo

Notes:

- The idea is to provide the environment to the replaced process

- The environment is strings of the form key=value

- An array of strings

- A parent can influence the environment of the child, this is yet another way of communicating with a child process

MAKEFILES=foo printenv

- We are overriding the child's environment variable

Note how you can define your main function in C++:

int main(int argc, char** argv, char** envp) {

for (char** p = envp; *p; p++) {

printf("$s\n", *p)

}

}

- Will print the whole environment

Exec family of functions: execv()

execv() receives a vector of arguments that will be available to the executable file. In addition, the last element of the vector must be NULL.

int execv(const char *pathname, char *const argv[])

#include <unistd.h>

int main(void) {

char *path = "/usr/bin/echo";

char *const args[] = {"echo", "Hello world!", NULL};

execv(path, args);

return 0;

}

$ gcc execv.c -o execv

$ ./execv

Hello world!

Exec family of functions: execvp()

execvp() looks for the program in the PATH environment variable.

int execvp(const char *file, char *const argv[])

#include <unistd.h>

int main(void) {

char *file = "echo";

char *const args[] = {"echo", "Hello world!", NULL};

execvp(file, args);

return 0;

}

$ gcc execvp.c -o execvp

$ ./execvp

Hello world!

...

Creating new processes

The following program creates a new process by invoking the fork() system call.

It also uses system calls getpid() to get the calling process’s ID and getppid() for the parent’s ID.

The following is the output when run twice:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello!! My ID is %d, my parent ID is %d.\n",getpid(), getppid());

pid_t pid = fork();

printf("Bye!! My ID is %d, my parent ID is %d.\n",getpid(), getppid());

return 0;

}

davidkebo@linux:~/code/week4/forks\$ ./a.out

Hello!! My ID is 75189, my parent ID is 74907.

Bye!! My ID is 75189, my parent ID is 74907.

Bye!! My ID is 75190, my parent ID is 75189.

- Note after

fork()the PID is the same! so that is why the second line looks the same

/CSCE-313/Lecture/Visual%20Aids/Pasted%20image%2020260206143704.png)

Notes:

- Shell is the one process that spawned the program

- Note we are invoking getpid() before we fork

- How do we have a parent before a fork?

- The parent of our program is the shell, it created you!

- There is a whole process tree that the OS has before you even open your first application!

- If we close both the parents(shell and fork caller), the who will be the parent of forked child?!

- It would be assigned to

init? - ...

- It would be assigned to